History is littered with famous families, of brothers and sisters who excelled in their fields and made Mama i Papa proud in the process. You’ve got the Harts, the Kardashians, the Warners, the Jacksons, the Dudleys (ahem) and more, the Baldwins, the Kennedys, the Bradys, the Strangs, Bros, the list goes on and on and on. In the world of Albanian education, one name stands proudly above all others — Qiriazi. Or Kyrias, if you’re talking from a Greek perspective. I’m not, so I’m going with Qiriazi.

The Qiriazi family was a very important group of siblings from Bitola, although it was called Manastir at the time (mid to late 19th century, for reference). There were 10 children in the troupe but four of them shone brightest, a pair of brothers and a pair of sisters who did more than most to bring education to the beleaguered Albanian population of the Rumelia Eyalet, siblings who made the most of their opportunities to lift an entire people out of the darkness and into the light, although please read that as more of a ‘from not educated to educated’ sort of thing.

I’ll start with Gjerasim Qiriazi, because he was the oldest and that makes the most sense. He was the founder of the Protestant Church of Albanian as well as the Kosovo Protestant Evangelical Church, but it was his dedication to publishing and education that really stood out. He was singled out from a young age by visiting American missionaries and sent to study at an American Bible College in Samokov, not far from Sofia (Bulgaria). Gjerasim flourished, and upon graduating he was offered a job by the British and Foreign Bible Society, a position that saw him installed as a teacher in the Albanian city of Korçë, which was something of a hotbed for Albanian nationalists looking to form their own state. Qiriazi began writing an Albanian grammar as well as preaching in his native tongue, growing his reputation with every sermon and every song.

That reputation got him in trouble in 1884, and by ‘in trouble’ I mean ‘kidnapped by bandits in the hills above Lake Ohrid’. The bandits were Albanians who weren’t particularly chuffed about what Gjerasim was saying, and they saw his lofty position among the foreigners as easy money, but the government wasn’t interested in paying the ransom and thus Gjerasim found himself interred for six long, miserable months. Being captured by bandits sounds rubbish at the best of times but in the late 19th century? In Southern Europe? Nah, I’ll pass. Gjerasim was constantly moved throughout the time, abused, beaten, blindfolded and treated with absolute disdain. The teacher was eventually released, but not before irreparable damage had been done to his mental and physical health.

It may have been the whole ‘detention’ thing, but Gjerasim moved forward quickly with his educational plans. He and his sisters (who I’ll get onto shortly) were dismayed at the low standard of life that Albanian women were seemingly born into, and quickly focused all their efforts into improving everyday life in that area. Korçë thus became home to the very Albanian girl’s school, opened in October 1891 and so popular that a bigger building had to be found less than a year later. The Greeks were adamantly against the whole endeavour, but the genie was not going to be put back in the bottle. Gjerasim worked night and day but the toil of his capture caught up to him, and he died of pleurisy at the age of 35.

Which leads me to Sevasti and Parashqevi, the so-called Mothers of Albanian Eduction. Sevasti was the elder of the two — hence her name getting top billing in that first sentence — and she followed in her brother’s footsteps, namely in getting the opportunity to study under foreign eyes at the American High School in Manastir. She was noticed by Naim Frashëri (an Albanian civil servant and historian) and whisked off to the American College of Constantinople, the first Albanian woman to receive that privilege, before returning to her homeland in 1891 to combat the distressingly high level of illiteracy among Albanian women. That level? 90%. Too high, by any metric. Sevasti wanted to improve the number of girls attending education full stop, as well as going all in on changing the very mentality in the community, a backward way of thinking that put barriers in the way of any young girl looking to get an education. She opened the girl’s school with her brother and set about publishing textbooks and other forms of educational literature. She was well on her way to achieving her goal, before World War I got in the way of it all.

Sevasti eventually left for the United States alongside her journalist husband Kristo Dako (and his moustache), but the lure of her native soil was too strong. Once the fighting was over the couple returned home, continuing the fight against illiteracy until another war got in the way, this time World War II. Sevasti and her sister (who I’ll get to shortly) were arrested for antifascist actions and thrown into the Banjica Concentration Camp in Belgrade, although both Sevasti and Parashqevi managed to survive. Sevasti’s husband was horrifically persecuted by the communist government following the war, which of course means Sevasti was horrifically persecuted by the communist government. Both of her sons were thrown in prison, one died. Sevasti passed soon after.

So, Parashqevi. You’ll remember that Gjerasim and Sevasti opened a girl’s school in Korçë in 1891, well, younger sister Parashqevi was also involved, despite being just 11 years of age. She was a trailblazer, an understatement and then some, but Parashqevi identified her passion early and threw herself into it. She was dedicated to the Albanian alphabet and the written-form of her language, a noble passion, and she was born into the right family to get things done. She buttressed her teaching with organisational activities, establishing more schools (including night schools) across the Albanian population and setting up libraries wherever she went. But the alphabet remained at the centre of her work, and she was present at the Congress of Manastir, the only woman no less. The congress was an academic conference held in the city to standardise the Albanian alphabet, although the existence of two of the things shows how successful it was. Nonetheless, Parashqevi Qiriazi was the only woman in attendance.

Parashqevi left Manastir once it was occupied and eventually found herself in the United States, although she too couldn’t resist the temptation of home. Her life followed that of Sevasti’s following the war, working further to improve the lot of ladies in the Albanian lands before being arrested for anti-fascist activities during World War II, managing to survive a stint in Banjica camp. She, too, was widely persecuted by the communist government after World War II, living in relative obscurity before being somewhat rehabilitated just before her death in 1970.

There was also Gjerg, the other Qiriazi brother, the man who founded an Albanian printing press, published an Albanian newspaper called Bashkim’ i Kombit as well as Albanian-language literature and poetry. I’d love to get into his life story but I’ve already written 1,200 words. Bitola week must continue. The Qiriazi siblings did more for Albanian education than any other family of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

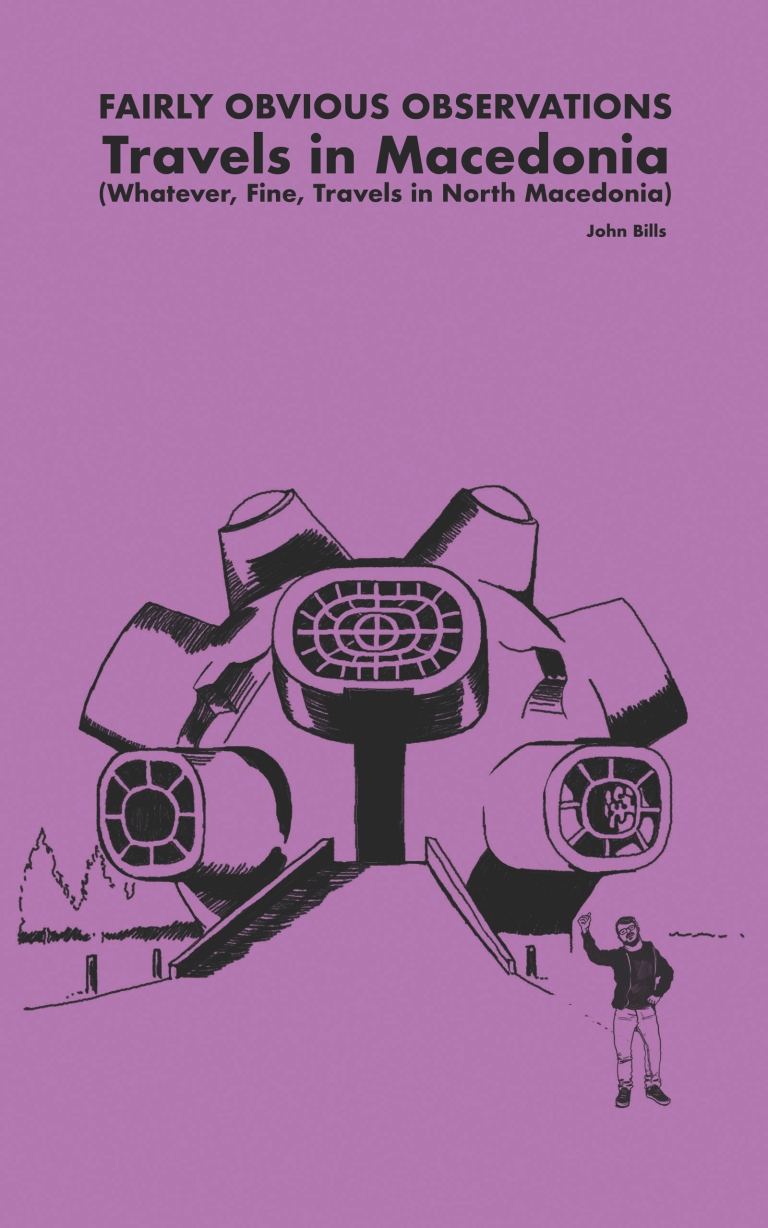

Working out who you are is difficult at the best of times, but have you ever tried to do it while working out the identity of a country squabbled over from the beginning of time, or at least ages ago? John Bills did just that with a trip through Macedonia (fine, North Macedonia), encountering local drunks in Kumanovo, beautiful architecture in Tetovo, absolute bliss in Kruševo and absolute confusion in Skopje along the way. ‘Fairly Obvious Observations’ is the story of that journey. It is available in digital form at www.poshlostbooks.com.